In West Bengal’s Purulia, a tribal homemaker builds a free school from scratch, bringing education to 45 children in a remote village.

Nestled in the Ayodhya Hills of West Bengal’s Purulia district, far from the hum of city life and out of reach of most government initiatives, something extraordinary is unfolding. In the tiny tribal village of Jiling Sereng, 30-year-old Malati Murmu, a homemaker, is quietly rewriting the script of rural education — with no formal training, no official title, and no funds.

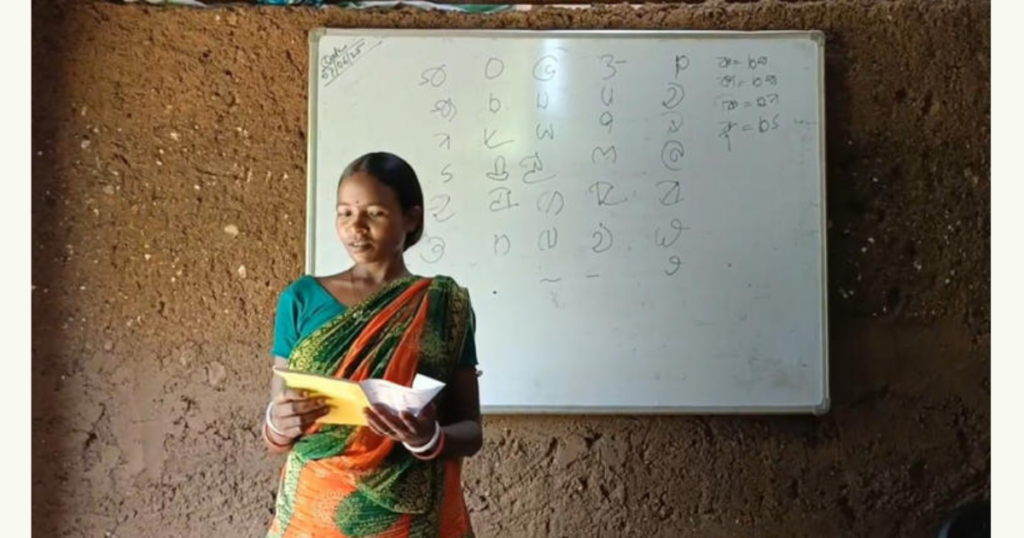

Her school doesn’t have painted walls, a proper roof, or even desks. It’s made of mud and tin sheets. There are no blackboards or staff. But every morning, 45 eager children arrive, armed with nothing more than curiosity and a desire to learn.

This is not a government project. No MLA came to inaugurate it, no NGO funds it. It began with one woman’s decision to step in where the system had stepped out.

From Homemaker to Educator

When Malati arrived in Jiling Sereng after her marriage, she noticed something missing — no children went to school. Despite the presence of a government school in the vicinity, many families, especially those from the tribal Santhal community, were not sending their children. The reasons were many: distance, language barriers, poor infrastructure, and a general disconnect between the school and the community it was meant to serve.

“I couldn’t sit by and do nothing,” Malati recalls. “I started by gathering a few kids at home, just to teach them basic letters and numbers.”

What began as informal lessons in her kitchen slowly gained attention. The children were enthusiastic, and parents began to see the difference. By 2020, with help from local villagers and her husband Banka Murmu, Malati built two small mud classrooms next to her house. That’s when her kitchen classroom became a full-fledged free school.

Learning in Their Own Language

One of the school’s standout features is that Malati teaches in Santhali, the language of the local tribal community, using the Ol Chiki script. For many children, this is the first time they are learning in a language they speak at home. This cultural connection has made a world of difference.

“Now my children read and write in Santhali,” says Sunita Mandi, a mother of two students. “That was never possible before. The government school teaches only in Bengali.”

This culturally rooted approach not only promotes literacy but also instills a sense of identity and pride in the children.

A Community Effort Without Government Support

Malati’s school is a collective story. Though she’s at the center of it, the village stands behind her. Parents help maintain the classrooms. Her husband handles logistics and supports her dream. And the children? They arrive daily, some walking several kilometres, just to attend class.

“We don’t ask for anything,” Malati says. “We don’t charge fees. All we want is that the children show up, and they do.”

Even as she raises her own two children and manages her household, Malati finds time every day to run the school. With no official salary, no support from the state, and minimal resources, she has created something that bureaucracy has failed to deliver: real access to learning.

More Than Just a School

In a time when public education is under fire for crumbling infrastructure and absentee teachers, this mud-hut school stands as a quiet rebellion. It’s a testament to what one person’s commitment can do, even in the absence of policy or planning.

“There’s a government school nearby,” says Banka Murmu, “but we wanted something of our own—something that understands us.”

Malati’s story reminds us that education is not just about classrooms or curriculums—it’s about care, connection, and community. In Jiling Sereng, a school wasn’t built by officials or funds, but by a tribal woman with a vision and a heart full of courage.

Sometimes, real change begins not in offices, but in villages. Not with budgets, but with belief.

Also Read: 95% of Karnataka schools adopt new teaching methods, but students are still falling behind